Personal Finance. Simplified

Helping you plan your finances better.

2nd

most influential

financial services brand

150,000+

Monthly readers

100,000+

Happy investors

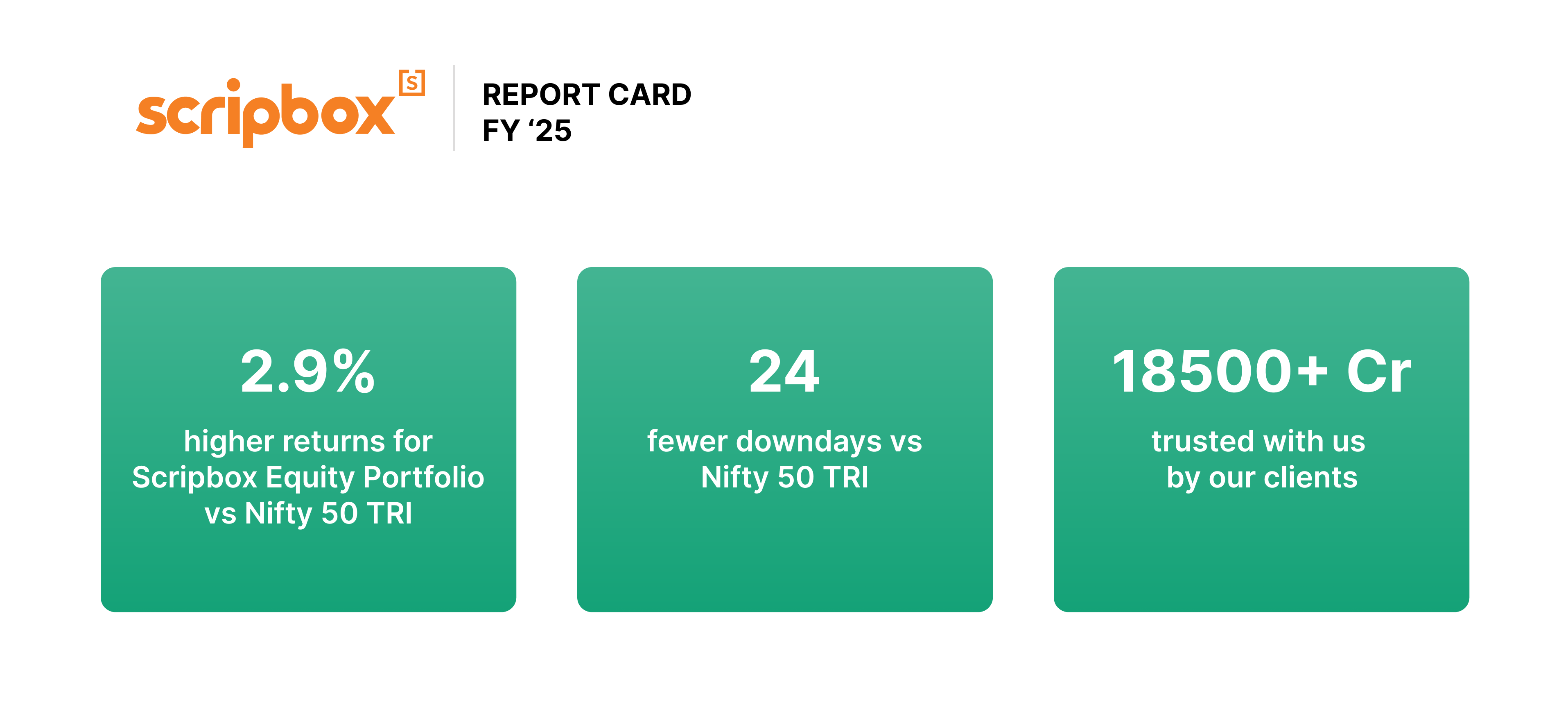

18,500 Cr+

AUM Handled

From the

Editor's Desk.

Our Finance Planners

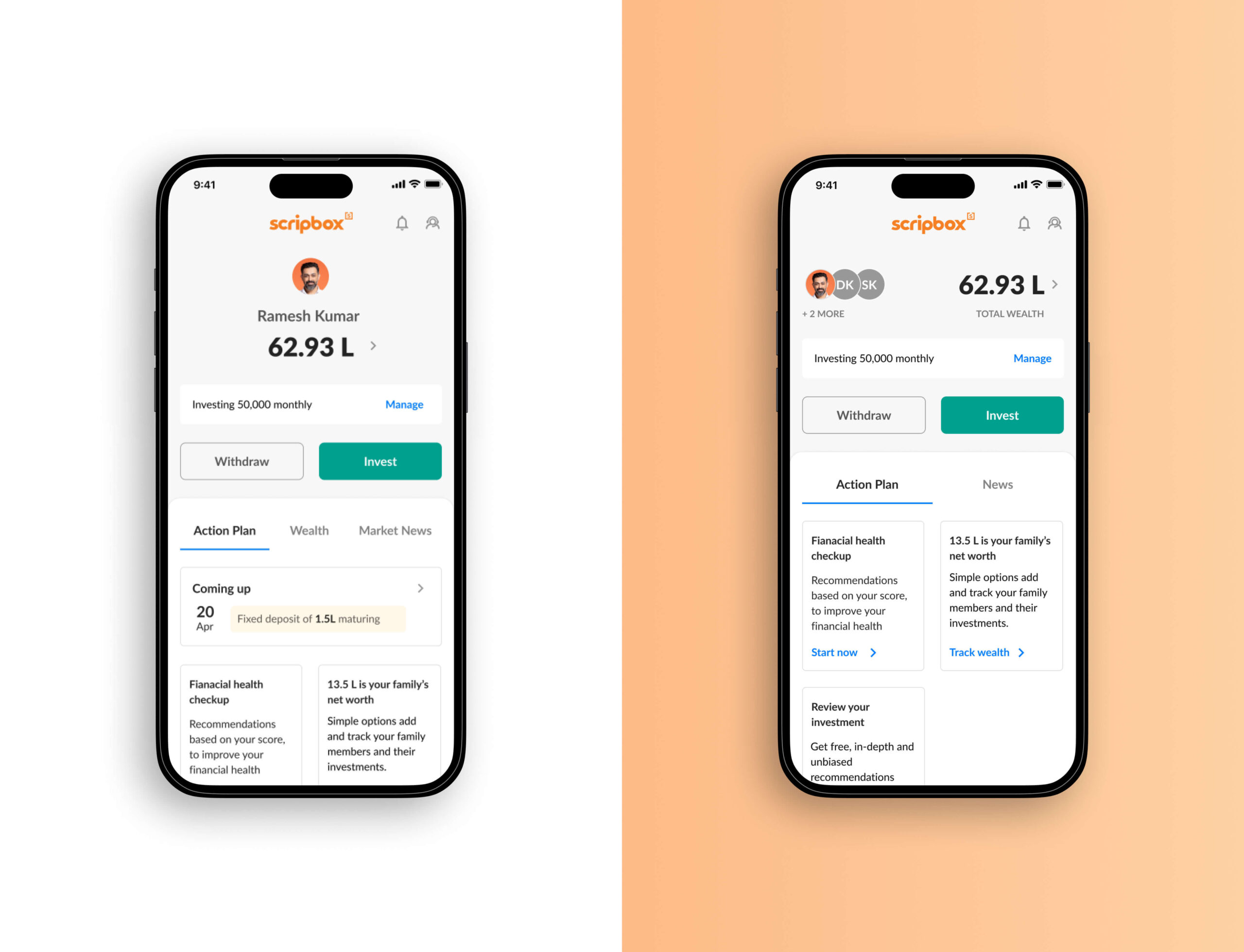

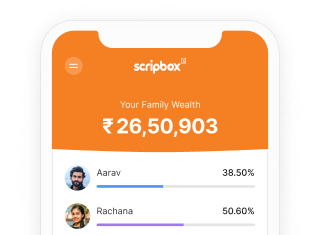

One home, and one app, for all your wealth

View, analyse, manage, and invest your and your family's wealth with the all-new Scripbox App.

One home, and one app, for all your wealth

View, analyse, manage, and invest your and your family's wealth with the all-new Scripbox App.